This is the final part of my three part cloud trilogy:

- AWS vs Azure

- Lock-in

- Pricing (this post)

Pricing

As mentioned in the first post in this series, cloud hosting may not be the best value option for you. Dedicated or co-located hosting can be a far cheaper option if you have a very consistent load profile and have the skills to manage the servers. If you don’t need the convenience of cloud hosting (being able to instantly create a new server and scale up quickly to meet spikes in demand) then alternatives might be better.

There are ways to reduce your bill (covered later in this post) but it’s hard to compete with the price / performance characteristics of bare metal. Hybrid approaches are available and I’ve built systems that combine dedicated VPS hosting with cloud instances, but this is beyond the scope of these posts.

I won’t cover Google’s cloud offerings either, but they may offer a price advantage depending on the workload, as they have a free quota on some products. Pricing also changes very regularly due to competition and reducing hardware costs, so it’s best to stay agile (see the previous post in this series).

EC2

For AWS I’ll focus on the Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) Virtual Machine (VM) service, as I have the most familiarity with it, and many other services base their prices on the underlying resources of it. However, you will also want to consider storage and data transfer costs, which I cover a little below. There is a comprehensive open guide here.

I gave this presentation a few years ago and while a lot has changed much still holds true. Specific prices aren’t shown as they change frequently but the relative costs and ways of reducing your bill are still valid.

There are many types of EC2 instance and there is a third party list here. I’ll focus less on the hardware type and more on the other variables. Clearly you shouldn’t over provision more resources than you need for your application. You can always auto-scale to additional instances if you have built your app correctly.

There are many other factors that affect the cost of an EC2 instance. Let’s cover them in turn as it can be very confusing.

Operating System

Some instances attract a premium due to the OS licensing. Windows is obviously more expensive than Linux but some enterprise Linux distributions (such as Red Hat and SUSE) also cost more. Although these are all still included in the free tier.

You could use free alternatives to Red Hat such as CentOS or Amazon Linux. Or you could use Ubuntu Server if you prefer a Debian based distro with the apt package manager.

An instance with SQL Server will cost more again than vanilla Windows. There are a few versions of SQL Server to choose from. You could install the free express edition on a plain Windows instance but it may be more convenient to use RDS (which now supports Multi-AZ for SQL Server, but not Read Replicas). SQL Server 2016 will be ported to Linux, so that could be interesting in the future.

Region

The geographic region where you locate your instances also has an impact on the cost. This is usually due to the scale of the site and the cost of electrical power in the area, among other things. For example, the Virginia and Oregon sites are cheaper than California and the EU.

When considering location it is prudent to think about the environmental impact, as you don’t want to host in a cheap region that gets its power from dirty coal stations and contributes to climate change. However, you should also aim to locate your servers close to your users for high performance.

Microsoft claims it is “100% powered by renewable energy” whereas for Google and Amazon this is still just an aspirational goal. Chalk one up for Azure, which is impressive considering that they have the most regions.

Instance Type

Billing type is where the biggest savings can be made, and the most complexity lies. It should not be confused with the size / hardware type of instances.

On-Demand

On-demand instances are the default option and are also the most expensive. They offer the greatest flexibility but are a bad choice for a server that is going to be up for an extended period.

Spot

Spot instances can be cheaper but are not suitable for normal workloads. They are good for performing computation that is tolerant to failure, for example analysing large datasets. You are effectively making use of unused capacity and the price changes depending on demand. Your instance could disappear at any point so you need to build your software in a certain way to take advantage of them.

Reserved

Reserved instances are no different to on-demand instances apart from the way you pay for them. You can assign a running instance to reserved without altering it or transfer reservations between them, as it’s just a billing feature. Reserved instances can save you a lot of money if your servers are always on for an extended period, but they are also the most complicated category.

The exact options have changed a little since I wrote the deck above but it’s still fairly similar. There are still three usage options and two timespan terms. In total there are now eight options to choose from, in addition to the permutations of instance hardware type, region and OS.

Light

Light usage is now called “No Upfront”. This is good if your server will be on some of the time and you can commit to this for a year or more. No upfront isn’t available on the standard three year term but is on the new convertible term.

You don’t have to pay anything upfront but you will get a bigger saving if you do. These plans were called medium and heavy.

Medium

Medium usage is now called “Partial Upfront”. This is good if your server is on for most (but not all) of the time. It sits between the other two and is available on all terms.

Heavy

Heavy usage is now called “All Upfront” and is a good choice for always on servers. As the name suggests, you pay everything upfront and your equivalent hourly rate (if you were paying by the hour) is significantly reduced. You are effectively paying in advance and it will cost you even if your instance is not on.

1 Year

You can reserve your instance for a minimum of one year but if you can reserve for longer then you will enjoy greater savings. However, you should consider that prices may reduce in that time. AWS have a history of regularly cutting prices.

3 Year

The three year term offers the highest savings but obviously ties you into a longer commitment. There is a new convertible term but this offers lower savings than the standard one, although you don’t have to upfront anything.

Deciding what options to choose will require some calculations and analysis based on your use case. Remember to account for potential price cuts in this.

Dedicated

Dedicated hosts are a bit different and guarantee that you are the only tenant on the VM host. I won’t go into this much as you may as well use a dedicated server for this purpose.

S3

Simple Storage Service (S3) is, oddly enough, Amazon’s storage service that can also host static websites. It has a few frequency settings (including a new infrequent access option) and a couple of redundancy settings that alter the cost. Price also depends on region, as with EC2.

S3 offers a reduced redundancy option that reduces what you pay for the storage. Amazon will keep your files in less places so this is only suitable if you have a backup somewhere else. It is also worth compressing your files to save space.

If you don’t need to access your files frequently and they are just archives then you could consider using Glacier or the newer infrequent access storage class. These are clearly not suitable for hosting static websites though.

If you are hosting a site then you will want to use a Content Delivery Network (CDN) to reduce the data transfer charges. For example, data transfer to Amazon’s CloudFront is free (but you pay for CloudFront).

You can also compress your assets to save bandwidth (in addition to saving storage space). You can gzip static files with maximum compression, set the HTTP content encoding header to gzip and let the browser do the decompression. There is a lot more to say on compression (especially of images) but that would be veering off topic, so if you are interested then you can read about this in my book.

Azure Blob Storage can also serve static files over HTTP. However, as it can’t serve a default page for a folder it isn’t as useful for hosting static sites.

Azure

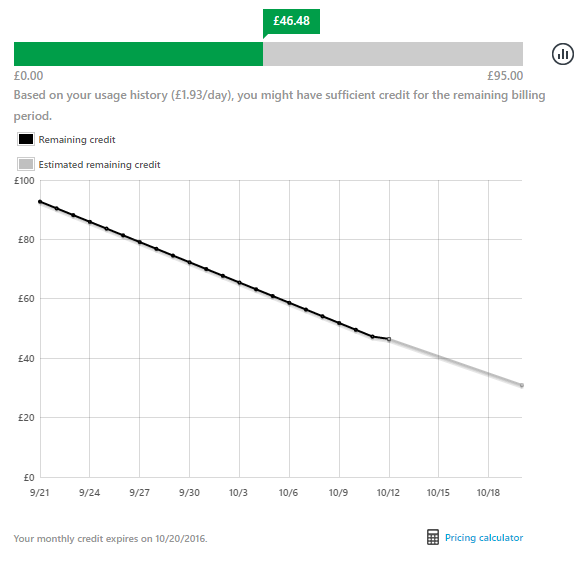

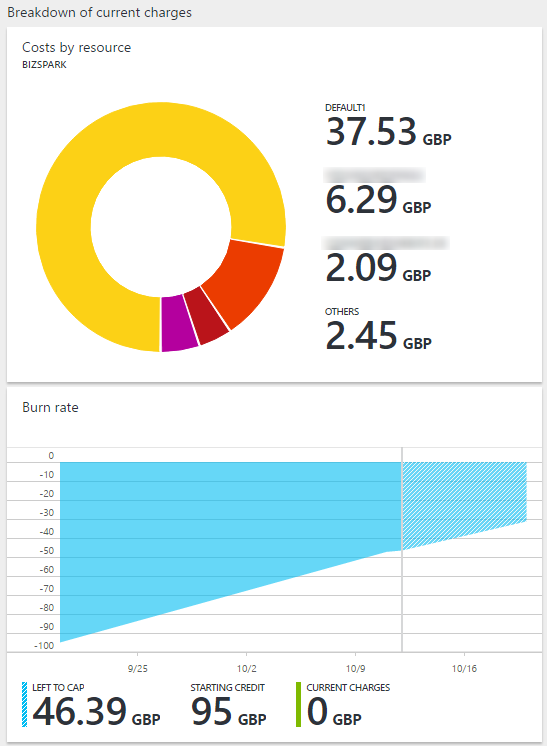

Azure has a slightly different billing model for some plans. Rather than being billed for what you’ve consumed you can use up credits. This allows you to manage your outgoings and you get nice burn-down charts.

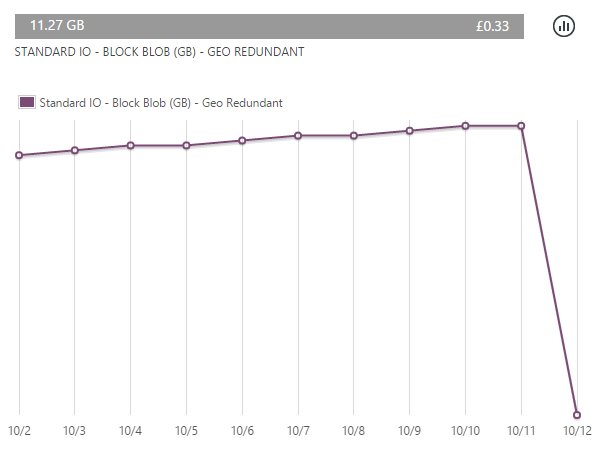

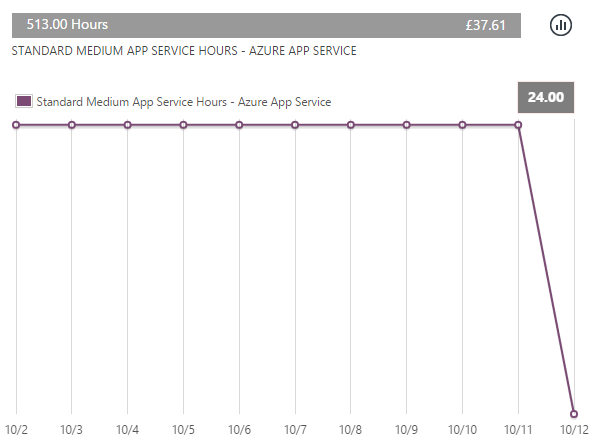

This is broken down into the various charges so you know where the money is going. For example, app service hours hosting a website and data usage on blob store.

A good way to keep a handle on these costs is to set upper limits. For example, use auto-scaling but set a maximum number of instances and use auto-backup but set a retention period to clear out old copies.

The new portal shows you how your costs are split across different sites.

If you enjoyed reading this, or at least found it useful and interesting, then you will probably like my book on how to make high performance web apps. It includes plenty of discussion on cloud computing, compression, CDNs and cost. The book covers how the choices you make affect the performance and agility of your application, and in turn the happiness of your users.

I’m also available for hire.